Remembering Robert Kee: 1919-2013

I owe a personal tribute to Robert Kee, the writer and broadcaster, who has died aged 93.

It was Robert who gave me my first real break in journalism and taught me much about what I came to admire about the profession. The year was 1977. Robert was planning a documentary for the excellent Yorkshire TV on Spain after Franco. Born in Madrid, and bilingual in English and Spanish, I had been juggling with Marxism , Spain and Latin America as a student , and had recently left the London School of Economics with an MA in politics and government. He picked me as one of his researchers.

It was the days when TV budgets were limitless and the unions’ ‘closed shops’ still had a habit of proving counter-intuitive. Having obtained an NUJ free-lance card, I roamed Spain for two months with a generous expense account and only the vaguest of instructions from the programme makers. I then presented Robert with a schedule of scenes and interviews which I hoped would help him answer the essential question: Could democracy survive, and, if so, in what form?

Once shooting got under way, I realised just what a real professional Robert was. Having befriended Professor Hugh Thomas-author of the seminal Spanish Civil War history-, he was well briefed on Spain’s disastrous legacy of intolerance, and had read himself further into the subject with his own extensive reading of newspaper cuttings.

Luckily we concurred in our basic thesis that Spanish democracy was struggling to free itself from its totalitarian past after a dying Franco had invested his succession in an unelected Bourbon Prince. We called the documentary ‘A Democracy has been arranged’, the paradox barely hiding our scepticism about the way we thought things would turn out.

Robert was not always an easy person to work with. He was a complex character –absolutely charming one day, while prone to fly off the handle on another, if things did not go as he planned, or if, as very rarely happened, he fluffed his spontaneous piece-to-camera lines. He could also be reduced to physical and mental paralysis when the black dog of his depressive side gripped him, at which point the whole production process ground to a halt and remained motionless for several days at a time. Without Robert’s central personality working at full strength, there were taped ‘rushes’ of film, but no driving narrative.

Luckily these mood swings did not prove the norm in Spain. For much of our time together, I witnessed an incisive and courageous journalist in action,with strongly held democratic principles, whether forensically recreating the scene of the murder by right wing fascists of a group of left-wing trade unionists, or conducting a discreet interview with a human rights lawyer about cases involving the torture of Basque prisoners.

While never frivolous, Robert never lost his eye for a good looking woman, and retained a sense of humour about Spain’s liberation from the dark years of Franco, as when, on Barcelona’s Ramblas, he had himself filmed turning the pages of a new magazine which, as he put it, seamlessly mixed political exposes, clever cartoons, and sex.

We found a common bond in our appreciation of ‘liberated’ Spanish culture (including good food and wine) while sharing in our occasional frustration with the ludicrous levels of manpower that a British broadcasting union insisted we should retain at all times.

And yet Robert was respected enough to go unilateral when he felt the occasion demanded, as when he gave me his blessing to take just one cameraman- a veteran from the Northern Ireland troubles- instead of a production team of fourteen- to cover a pro-democracy demonstration which politically unreformed riot police tried to suppress with terrible violence in Barcelona’s San Jaume square. “Get the shots, bugger the rest, and make sure you get out in one piece,” Robert advised me.

Much later I would reflect that much of Robert’s own fearlessness and liberalism predated his journalistic career . It drew on his WW2 experience as a young man, when he served with the RAF on bombing missions against Nazi Germany, was shot down, and escaped from a prisoner of war camp in Poland. He was later rearrested near Cologne-a subject he later drew on for a book he wrote once the war was over.

As well as being a TV broadcaster, Robert wrote novels and histories, among them his compelling account of Ireland- the Green Flag, which was made into another successful TV series.

After Spain, we lost touch for a while, until the Falklands War when I- as a foreign correspondent in Buenos Aires- and he as a presenter in London for BBC’s Panorama similarly struggled to feel dispassionate about a war we believed had been provoked by the lunatic ambition of a bloody military junta.

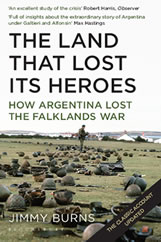

I sadly mislaid some time later a generous letter he kindly wrote me after the war was over. In it, he thanked me for sending him a copy of the first edition of The Land that lost its Heroes where I recounted my arrest on suspicion of spying by the military junta, and blamed the failings of British intelligence as well as the nature of Argentina’s militarised society for the invasion of UK territory that cost the lives of 649 Argentine military personnel, 255 British military personnel and 3 Falkland Islanders.

After that, circumstances conspired against more regular meetings although we occasionally bumped into each other on our way in or out of some London gentleman’s club many of whose members were as opinionated as he was, but rather less heroic. Robert belonged to a time when journalism across platforms could still be fun as well as demanding, while retaining its quality, and when it could still be a country for older, wiser men like him. More than thirty years older than me when we first worked together, my memory of him endures as an inspiration. May you rest in peace, Robert.

A wonderful obituary which reads very well. It portrays Robert Kee as an extraordinary person, a master in his field, and although I never met him, I know from the many times you mentioned it, what had an enormous influence your first assignment had on your career.

There is one point which intrigues me and I would appreciate your answer. Given you were very influenced by Marxist currents of thought while at the LSE, how did you then resolve the contradiction, as a young enthusiastic researcher, of the closed shop weighing so heavily on the creativity, spontaneity and work schedules during your journalistic mission? Every day you must have been witnessing the difficulties of a situation, where the “proletariat” (Union closed shop) who were being guaranteed work by the “ruling classes” (BBC), were making life extremely difficult (I love the account of the Union protocols being trashed so as to film a protest, a story covered by 1 instead of 14). Did have a serious re-think about Marxism on your return to the UK?