If in war the first casualty is truth, then the Falklands conflict, fourty years ago, provides an interesting case study.

This paper examines the extent to which a regimented society in Argentina was exploited by the military junta to provide a manipulated and distorted narrative of the Falklands War.

The aim was to give the impression that the war was not only justified in sovereignty terms but had God on its side. In the process a nation rallied behind a Project which in diplomatic and military terms was doomed to failure.

While there were efforts to control coverage on both sides of the conflict, the Argentine people and media were subject to the control and propaganda typical of a dictatorship, both repressive and crudely manipulative.

The tactics succeeded for a while in fuelling huge nationalist sentiment but in the end backfired as the lies being perpetrated gradually became evident, once the British armed forces, with the support of the small local population that had chosen to remain a democratic people attached to the UK, recovered the islands , and the junta’s campaign was exposed as a shameful betrayal of trust and a tragic loss of life. This was subsequently recognised under the enlighted post-war democratic government of Raul Alfonsin who saw to it that the Argentine military commanders were not lonely tried for human violations following the 1976 coup but also for their misconduct of the war against the British.

The paper draws from my experience as the only fulltime British foreign correspondent to be already posted in Argentina when the Falklands were invaded and who covered the war and its aftermath in Buenos Aires-a time I reported for the Financial Times , and the Observer between 1981 and 1986,and which firmed he subject of my first book The Land that lost its Heroes: How Argentina Lost the Falklands War.

As a fluent Spanish speaker, and a Latin American specialist, and a journalist with the prestigious FT , I had access to unrivalled sources throughout the war which allowed me to test the official propaganda with the reality of what was in fact happening in the highest echelons of power and also on the ground, often at some personal risk.

The paper examines the most memorable points in which the junta’s propaganda manifested itself, how the Argentine media conspired to portray unquestionably the official version of events, and the dangers that faced those who endeavoured to puncture the myths and the lies.

I would like to begin by noting that Argentina as a nominally catholic country was vulnerable to the influence, as it had been in various stages of its history, of Mother Church, not least certain bishops and priests that not only fuelled a strong sense of nationalism but also supported the military coup of 1976 and the juntas that ruled in the period leading to the Falklands War.

The symbiosis between Church and State gave the soldiers a sense of moral crusade and the junta the political approval on which their power rested. This was apparent from the first day of the war, when the commanding officer of the invasion forces, Real Admiral Carlos Busser, agreed to name the military operation to seize the islands Operacion Rosario. The feast of the Virgin of Rosario was established in 1573 by Pope Gregory X111 to commemorate the crushing defeat of the fleet of the Ottoman empire by a Christian alliance led by the Spanish commander Don Juan de Austria.

Worth recalling here that the victory of the Holy League is of great importance in the history of Catholic Europe following the Protestant Reformation , and its crucial importance in the defence against imperial expansion.

Busser had no doubt that the Godless protestant imperialist ennemy, personified initially by the islanders and seventy odd marines on the islands , was about to suffer an equally Virgin-sent defeat with the historic recovery of Las Malvinas.

The war was to prove the absurdity of such a presumption, not least the fact that the British Task Force included many Catholics and that that one of the unsung heroes was the British chaplain on the Falklands Monsignor Spraggon who while opposed to the military occupation and its violation of the islanders’ human rights opened his church’s doors to friends and foe.

The equation between Argentine sovereignty and holy conversion , a powerful propaganda vehicle, had its precedent, and was deeply engrained in the Argentine national consciousness.

Argentine history books devote many pages to the first Spanish missionaries to the Falklands islands and their Argentine successors; the priests are portrayed as picture book saints laying their sacramental rock in the heathen land. What is perceived as a subsequent decline of civilised life on the islands is blamed on the spiritual emptiness of British Protestant colonialism.

Building on this tradition, the junta and its collaborators expanded the concept so that the invasion and its aftermath was presented to the population and the outside world as a holy war where everything was permitted for the sake of the just cause.

Thus, just as some Bishops and priests had blessed the defence of so called Western Christian values during the repression of political dissidence following the coup, they now established the theological validity of ‘Las Malvinas’.

“The Gaucho Virgin is Mother of all , but is in a very special way the mother of All Argentines, and has come to take possession of this and, which is also her land.”

Thus did a military chaplain Monsignor Desiderio Colino bless a statue of the Virgin of Lujan, along with eight crucifixes, various Generals, and an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 troops on April 7th 1982 when an Argentina military governor General Marion Benjamin Mendez, took charge of the islands.

The junta propaganda machinery took hold of the Argentine media, contrasting the venerable nature of the ceremony with graphic examples of the ‘immoral’ symptoms of British rile, making much of the all the alleged evidence discovered in the British marine barracks when it was occupied by Argentine soldiers. The media reported, with a sense of moral outrage, that the barracks had been filled with pornographic magazines and videos.

In this Holy War, no Argentine churchman was perhaps as fanatical as Fr Jorge Piccinalli, a young priest who arrived on the islands on April 24th, 1982, to boost troop morale in the face of the growing awareness that the war might be for real.

In an interview with Argentine TV journalist Nicolas Kasanzew soon after his arrival, Piccinalli said that the time had come for Argentina to have some real heroes. “I’m not talking about footballers, “he told Kasansew, “I mean heroism in the Greek sense of the word.”

Piccinalli stayed on the islands until the end of the war, imbedded with the Argentine troops and celebrating mass near the trenches. I quote from one of his sermons , published after the war, one deserved to be quoted at length. There can be no better illustration of the uses to which religion can be put at a time of war:

“We the Argentine people who are Catholic, Hispanic and Roman, have today ensured the reconquest of a piece of territory on behalf of a nation that has Christianity in its origins…..

We have to see it as a war fought for the defence of our Nation and for Jesus Christ. We have to take in our hands the Holy Rosary and commend ourselves to the Holiest Virgin who is always going to be with us. Because the fatherland has been consecrated by the Virgin of Lujan. And the Virgin of Lujan and the Virgin of Rosario are going to protect us, you can be certain of that. And that rosary which you have round your necks and in your hands is a great instrument. It is a great defence …That is why we have to put our trust fully in God, totally in Christ and in the holiest Virgin, queen and lady of Las Malvinas, which is Argentine territory….”

From that moment on, Argentine pilots hung rosaries round their sights before shooting their missiles at the British Task Force. Bits of British fighter jets –those claimed to have been shot down- were dedicated to the Virgin of Lujan, soldiers carried bibles to protect themselves from bullets, and military chaplains regularly broadcast to the Argentine mainland proclaiming their troops as blessed heroes .

The theme was enthusiastically taken up by Esquiu, a traditionalist Catholic Argentine weekly which throughout war was sold in churches up and down the country. One cover story showed a map of Argentina including the islands surrounded by a rosary with an editorial which focused on the Malvinas as a just war: ‘We Argentine Catholics fight for peace, but we also know that the commandments tells us to love our country, and of necessary, give up our lives for it. In the present circumstances, the commandment is quite clear: if they attack us, we have to defend ourselves.”

The Argentine Church, not only blessed the invasion but refused to acknowledge that human rights was an issue. “All Argentines, believe our cause is just,” wrote Fr Agustin Puig, editor of Esquiu, “I think the good God is content with this faith of ours.”

During Sunday masses, priests dedicated their sermons to a call for generous contrbutions to the Patriotic Fund which was collected by the military for their war effort although never publicly accounted for.

In their only major statement issued as a group during the war, the Argentine Bishops expressed their fear of a war of unforeseeable consequences as the Task Force approached the islands. But by their emphasis on the justified defence of Argentina’s sovereignty, the Bishops implicitly gave the junta the green light to proceed as it saw fit.

Significantly the few Churchmen who refuse to tie the official were censored by the authorities. Bishops Novak and Nevares, both of whom had been outspoken critics of the junta’s human rights record, wrote a paper urging the Church to be more strident in their opposition to the junta’s military action over the islands.The paper was supressed by the hierarchy.

The regimentation of Argentine society, as reflected in the media, was evident from the day Argentine troops invaded the islands. Newspapers which, fourty eight hours before at the end of March 1982, had reported at some length on the brutal repression of a prodemocracy demonstration in the Plaza de Mayo , instantly whitewashed any critical reference to the regime and joined in the mass euphoria.

Anyone reading the local newspapers or watching the TV at the time would have been left with no doubt that the military occupation had been planned at short notice and was simply a defensive reaction to growing British hostility over the islands; no Argentine journalist attempted to investigate further back than the South Georgia incident,where a naval unit led by a notorious torturer and killer Captain Astiz can raised the Argentine flag in late march 1982 , to see whether the invasion has been long planned by the junta, with an eye to distracting the country from domestic issues and strengthening popular support for the military rule .

Undoubtedly many Argentine journalists shared the sentiment that every Argentine , whatever his or her profession, felt it their patriotic duty to support the recovery of Las Malvinas-and the regime made every effort to oppose a more nuanced narrative.

From the moment the British Task Force ventured forth, the Argentine Chiefs of Staff issued strict guidelines governing the Argentine media. For ‘reasons of national security’ journalists were advised to refrain from publishing any material that ‘attacks national unity’, ‘helps the psychological objectives of the enemy’, or ‘gives information on military positions other than those officially confirmed.’ Argentine journalists who had survived years of repression were left in no doubt as to what the consequences for their physical well-being might be if they didn’t tow the official line.

True newspapers Argentine broadsheets La Prensa and La Nacion published regular coverage-most of it a fair refection of what was appearing in the British media-from their correspondents in London, Maximo Gainza and Eduardo Crawley

But reporting in Buenos Aires proved more challenging as James Neilson, the editor of the English langage Buenos Aires Herald discovered early on in the war when he condemned in an editorial the Argentine military action. For ten days the newspaper, accused of antipatriotic activities, was taken off the streets as a result of a strike by the newspapers’ distributors supported by the junta.

Then the threats began. An anonymous caller rang the newspaper’s offices to warn that ‘for every Argentine soldier that falls, three British will be killed.” The caller left it unclear whether he referred to soldiers or civilians or both, but the threat, coming as it did in the wake of the sinking of the Argentine battleship Belgrano, caused alarm and fear not just in the Herald staff but throughout the 17,000 Anglo Argentine community living in Argentina. Another call threatened Neilson with death for himself and his family.

The British journalist had been subjected to similar intimidation ever since he had taken over as editor on 1978 when his predecessor Bob Cox was forced to leave Argentina. Nielsen was sufficiently convinced of the seriousness of this latest threat to put himself and his family on the next plane out of Argentina, thus joining the list of Herald journalists who had been forced to leave the country because of their outspoken views .

In a book published both in Britain and Argentina after the war, the London-based Latin American Newsletters reproduced the official communiques issued throughout the conflict by both the Argentine junta and the British Ministry of Defence

By their own admission in the introduction, the authors set out to destroy what they alleged was one of the major myths of the war: that the British version of the conflict was more truthful than the Argentine. It was simply not true, the authors insisted, that the ‘Argentines gave a triumphalist version, inventing victories and hiding failures.’

Other books on the media and the Falklands concentrated on the difficulties faced by Fleet Street and the BBC. Robert Harris, in a harsh attack on the British government concluded that the pre-internet Falklands War could well prove itself the last war in which the British armed forces were completely able to control the movement and communications of the journalists covering it. Such a view inspired some Argentine commentators to declare that the junta had in fact behaved more democratically than Margaret Thatcher.

In his best-selling account of the war as seen from Argentina,Sergio Ceron stated” “British fair play…is a concept invented by the English so that the rest of the world can recognise in them simply qualities they simply do not have. While London boasted of its freedom of the press, the fact is that within the Task Force there was much greater censorship than that imposed by the Argentine junta.”

Let us examine this claim more closely.

It is certainly true that in the first stages of the war the junta was often quicker and more concise in publicly recording events as they happened than the MoD’s spokesman Ian MacDonald.

I personally experienced this at the start of the conflict as a British correspondent in Buenos Aires having arrived in Argentina the pervious December in 1981. Alerted to the imminence of the invasion in time for the final edition of my newspaper on April I, 1982, I found the British Embassy as reluctant as it had been for most of the preceding weeks to concede that something dramatically out of the ordinary was amiss.

Meanwhile in London my night editor heard my suggestion that an invasion was underway with incredulity: surely, if the invasion was taking place, the Ministy of Defence, Number 10 or the Foreign Office would have briefed journalists in London was the question thrown at me. Evidently they hadn’t. It was not until six hours after I had picked up the first rumour of the invasion and ten hours after the Argentina public knew that the junta’s troops had landed on the islands, that the British government finally confirmed that the islands had been seized.

Subsequently, the junta was often first to confirm, usually with accuracy, an important military engagement, even if-as in the case of the sinking of the General Belgrano-where risked a public admission of a major strategic reversal, but also calculated that the sinking of the battleship –the Gotcha of the Sun’s infamous headline- would provoke outrage in Argentina and Britain as a disproportionate act of war.

Such nuanced propaganda however proved short lived. A closer look at the communiques of the junta reveals that once hostilities officially broke out on May Ist, there was a a conscious attempt both to exaggerate Argentine successes and discredit Britain’s military advances.

In fact the earliest and most blatant example of misinformation by the junta involved the recapture of South Georgia by the British on the 25th April 1982. As described in a series of official communiques to the Argentine nation, the defence of the islands by Argentine naval commandoes was portrayed as heroic.

The version put out by the junta was that that the defence had lasted several days during which the Argentine contingent faced overwhelmingly superior forces but put up a determined effort to fight until it had exhausted its defensive capacity. The end of Argentina’s defence of South Georgia was never officially recognised by the junta.

The last reference to military action in South Georgia was that the Argentine commandoes had broken up into smaller units and were resisting in the hinterland which was a lie. On 26th April, amid reports from London and elsewhere that the commando contingent had surrendered the day before, the junta issued a formal denial and warned Argentines to beware of a British campaign to confuse public opinion.

Had the communique been issued five days before it would not have been so far from the truth, since on that day a group of British special forces were forced to abort a helicopter mission because of bad weather. The incident was kept from the junta and from the British people. But coming when it did, the junta’s statement was little more than crudely managed misinformation , of the kind that would eventually backfire politically.

For the officer in charge of the Argentine defence – Alfredo Astiz,- was revealed one of the most notorious violators of human rights during the post military coup repression in Argentina , He had been sent to South Georgia hoping to earn himself a clean medal. Much later, when the navy chief Admiral Anaya was eventually tried for his misconduct of the war, he said of Astiz, later himself prosecuted for human right violations : “Never did it cross my my head that that young man would surrender: never.”

Official communiques in the last stages of the war confirmed the extent to which the junta grew to believe in its own propaganda, to the extent that it lost sight of the political risks involved in not telling the truth.

While swiftly confirming the landing of British troops in San Carlos Bay, the junta was equally quick to conjure up a vision of a heroic counter-attack, insisting at one point that the invading British were completely surrounded and on the point of humiliating retreat.

The policy of not admitting publicly that the British had taken prisoners of war was first adopted in South Georgia, where the existence of Astiz was simply censored out of all accounts after the surrender. Similarly at Goose Green on the Falklands on the 28-29th May the reality of Argentina’s defeat by the parachute regiment went unrecorded in the local media.

Until the very end of the war, the myth of a brave defence by troops led by General Mendez was maintained, although it subsequently emerged that the Argentine military commander had virtually conceded defeat from the moment the British established a beach head on Falklands soil.

The 14th of June 1982 was the day the Argentine nation experienced the full spectrum of emotion: from elation with the alleged heroic resistance to collective trauma at the realisation of humiliating surrender. Like a speeded up film, the official communiques came out one after the other, suggesting initially that the battle had only just begun and next that it was all over.

It is worth noting that the official communiques, distorted as they were, were the soft edge of the dictatorship’s campaign to ensure that the nation remained committed to the occupation or historic recovery of Las Malvinas.

Behind the scenes there were more sinister manoeuvrings aimed at media control in tactics used during the junta’s war against left wing guerrillas and political dissidents following 1976 coup. Throughout the Falklands War individual officers linked to the Argentine intelligence services attached themselves to newspapers and leaked their account of the war. Sometimes these ‘sources’ simplyade a point of ensuring that the communiques were treated seriously; but most if the time they time embellished here, invented there, bringing the propaganda war to new heights of invention.

Nowhere did the work of these unofficial spokesmen prove more effective that in the mass circulation glossy weekly magazines Gente and Siete Dias, which between them provided massive coverage in support of the Argentine military with little respect for fact checking.

Take a report published on the 6th of May 1982 by Gente insisting, complete with illustrations and alleged eye witness reports, that Astiz’s brave commandoes were still fighting it out in South Georgia, hiding in caves.

The same issue contained a report on an Argentine air force pilot’s kamikaze attack on HMS Hermes with a Pucara ground-attack aircraft. Not only did such an attack never take place but the pilot mentioned by name had in fact died five days before the report was published in a British attack on a temporary landing strip near Darwin. The Pucara had been hit before the pilot had time to get it airborne.

To flip through the pages of Gente and Siete Dias published during the Falklands War was to discover Argentina’s political culture in all its absurdity , and ideological confusion. If the magazines supported the Argentine military effort, they did so knowing that their circulation increased as they exploited the national mood.

But this was not serious war reporting but simply propaganda. For while the British Ministry of Defence had twenty-six journalists attached to the Task Force constantly bombarding it with requests for clarification and protests about censorship, very few Argentine journalists were allowed on the islands by the junta to cover the war, and those that were, were easily manipulated.

The junta dictated that only a select group of journalists witness the invasion and the swearing in of General Mendez as governor. Subsequently only four journalists were allowed to remain –two from the official news agency TELAM, one from the official state TV, and a fourth with BAI Press, a military run news agency of dubious professional status.

Other Argentine journalists found themselves covering the war from Patagonia in the south of the Argentine mainland the authorities subjected them to two regular rituals. The first involved pfoto-ops of freshly groomed and informed coscripts staging mock engagements with an unseen enemy. The next day photographs of troops in combat in Las Malvinas would appear in some of the newspapers and magazines; the fact that the photographs showed trees as well as men, even though the Falklands have no such trees, seemed to go unremarked , such was the average Argentine reader’s total ignorance about the islands.

Another had Colonel Esteban Solis, the official press spokesman of the Argentine Fifth Army , giving regular briefings on the progress of the war. Rather than explaining military operations, the briefing concentrated on the alleged depravity of British soldiers . Argentine journalists were treated graphic descriptions of alleged homosexuality and alcoholism with the intrepid Solis holding up empty bottles of ber, pornographic magazines and women’s underwear which he claimed had been captured from the enemy.

Let me turn now to the 500-odd foreign correspondents who were stationed in Buenos Aires during the Falklands War. Seldon in the history of modern journalism had so many hacks been under such pressure to report a war and yet been so far from the scene of actual battle. To the veterans of Vietnam and fresh arrivals from El Salvador-and there were many-the Falklands became a war quite unlike any other, without a recognisable front line and yet with the certainty of local colour adding to a pervading sense of insanity. There was were many an impassioned mass rally over a group of islands no one really wanted except a few hundred sheep shearers and a group of corrupt generals- but then Thatcher ordered her Task Force and things seemed to take on a different dimension. The whole world got involved or it seemed with all the shuttle diplomacy and the endless UN debates, the embargoes, and the arms sales. ‘Las Malvinas son Argentinas’ everyone kept screaming. But your average hack struggled to make sense of it all. The Argentine military kept the international media as controlled as it could, most of them holed up in the Sheraton hotel with three conditions: no trips to the islands, restricted travel and only authorised outside Buenos Aires, and a ban on the word Falklands being used in public. The afternoon briefing in the Sheraton by an Argentine military spokesman was regularly brought to an abrupt halt by a journalist from the Daily Express insisting on introducing he word Falklands whenever he asked a question.

While some journalists spent most of the war in the Sheraton, concocting stories as best they could with their non-existent Spanish, and close to zero knowledge of Argentine history or political culture, others went out further afield to find out what lay behind the apparent national euphoria-and once that happened the Argentine military regime started showing its nastier side.

On the 13th April 1982, three British colleagues Simon Winchester of the Sunday Times and Ian Mather and Tony Prime of the Observer were arrested on bogus spying charges and imprisoned in Tierra del Fuego for reporting on Argentina’s military build-up in Patagonia.

For the rest of the war, scarcely a week went by without a foreign correspondent being arrested. I myself and my wife were detained at Buenos Aires airport from where we planned to fly to the north of the country to the border with Brazil. We had planned an overnight stay near the Iguazu Falls, as a break from the stress of covering the conflict. I

had with me a match-boxed-size Minox sub miniature camera and a local map where I had marked the site of the old Jesuit missions. Our military interrogators wove an intricate conspiracy theory that we were spies setting up an invasion by British special forces. We released in a few hours thanks to a timely intervention by a senior naval officer friend who worked for the Argentine foreign ministry.

My wife and I were simply lucky. In that month of May 1982 some foreign journalists were arrested and expelled from the country. Others were abducted and beaten up by regime thugs before being released. Officially the junta professed its innocence, blaming such intimidation on uncontrolled elements of the security forces. Similar arguments had been used to excuse the ‘excesses’ leading to the disappearance of over 8,000 Argentines after the military coup of 1976- so it wasn’t a great comfort. The intimifdation was part of the machinery of repression, not an exception to it.

As I discovered after the war, the Argentine military in fact had secret plans to step ups their control of foreign journalist had the war continued longer than it did. Plans ranged from a mass expulsion order to selective assassinations of individual journalists.

But while the war lasted, the net effect of the Argentine manipulation of information was that the rest of the word found out the truth before most Argentines did -that it was a war that Argentina should never have embarked upon on, and had no chance of winning.

In Britain, Argentines were free to express their views-pro and anti- junta-both in newspapers and TV. Such debate was anathema in the Argentina of the juntas.

Meanwhile the more professional and investigative of the foreign correspondents managed to convey a better sense if what was going on than any Argentine journalist.They picked the brains of well-inforned dipomats, relatuves of soldiers and returning visitors from the Falklands to patch together a more or less accurate account of life on the islands and the growing problems facing the Argentine military as the British advanced.

In Britain and the United States the fact that the networks obtained more footage from Argentine TV than they did from their own organisations was celebrated as the first time in history that the media had been permitted to report freely the enemy’s view of the war. And yet none of that footage was ever seen by the Argentine public during the war, while individual offices secretedly made substantial sums of money trading the footage. Similar corruption involved the use of photograhs.

Let me draw to a close I would like to reflect why the junta efforts to ensure collective solidarity with its war effort found fertile ground. A sense of militarised ritual was deeply engrained in the political consciousness of a nation in arms. A cycle of national days, commemorating events of military grandeur had for long been part of the national calendar. During the Falklands war they were reenforced , providing a point of reference for commentators and government officials alike. In schools, history lessons ignored making references to the military’s record of human rights violations and focused instead on a narrative that aimed to justify Argentina’s claim of sovereignty over Las Malvinas and the military invasion as an act of justice. School children had their lessons constantly beginning and ending with renderings of the national anthem, with its rallying call t.o die for the just cause in glory.

Among the civilian population, emotional mobilisation was assured by the launching of the Patriotic Fund raising campaign in support if the war effort . On the 9th of May 1982 a 24-hour long benefit performance broadcast live nationally involved most of the country’s celebrities and donations that ranged from an accordion belonging the country’s most famous tango composer Astor Piazzolla to a chalice used by a priest in his first mass.

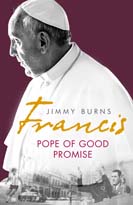

- Jimmy Burns is the author The Land that Lost Herors: How Argentina Lost the Falklands War